"From ideas to instruments": Prof. Jürgen Popp on the power of strategic partnerships, AI-enhanced photonics, and citizen science

Reading time: about 10 minuts

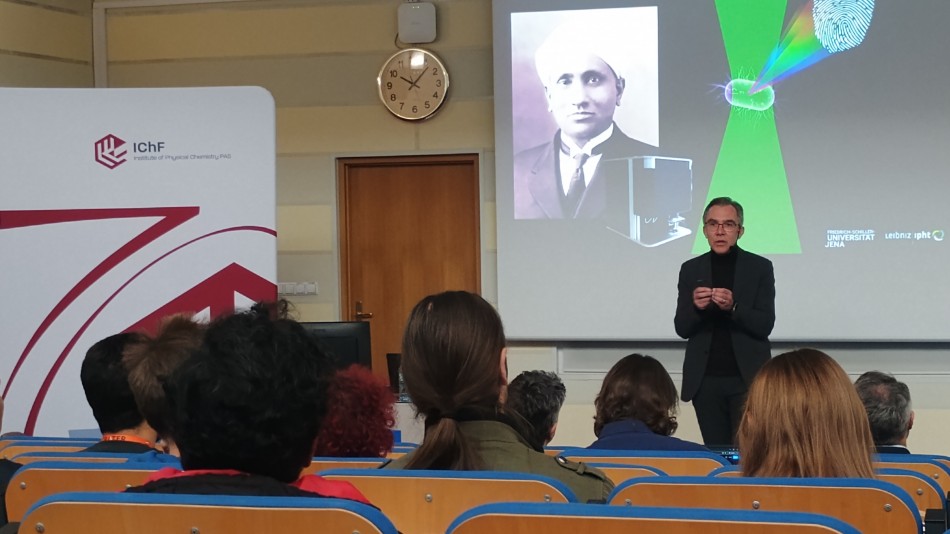

In late October 2025, the Institute of Physical Chemistry, Polish Academy of Sciences (IChF) had the pleasure of hosting Prof. Jürgen Popp, Scientific Director of the Leibniz Institute of Photonic Technology (IPHT) in Jena, Germany — our key strategic partner in Europe.

During his two-day visit to Warsaw, Prof. Popp met with IChF research teams led by Prof. Jacek Waluk, Prof. Agnieszka Michota-Kamińska, Prof. Maciej Wojtkowski, Dr. hab. Katarzyna Krupa, Dr. hab. Jan Guzowski, as well as many other scientists. He was accompanied throughout the visit by the Director of the Institute and its Professor, Prof. Adam Kubas.

The highlight of our special guest’s agenda was a lecture delivered as part of the Dream Chemistry Lecture series, titled "AI-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy: Translating Photonic Innovations into Clinical Diagnostics and Therapy." The event attracted an exceptional audience — the Aula was filled to capacity, with attendees even sitting on the floor. Prof. Popp's lecture generated extraordinary interest and inspired a vivid and insightful exchange during the Q&A session that followed.

On October 23rd, Prof. Popp gave an interview to the IChF PR Manager, reflecting on the value of international scientific partnerships, the societal role of research, the future of photonics, the growing relevance of citizen science, and the qualities that help young researchers thrive in today’s evolving scientific landscape. We present it below.

Do you believe that building strategic partnerships — such as between our institutes — is essential today for the development of science? And what makes these collaborations more than the sum of their parts?

When we look at the research we are doing at the IPHT in Jena, one of our strong focuses is on biophotonics — or, as we also call it, optical health technologies. This already means that our approach is highly interdisciplinary. From this perspective, strong collaborations are absolutely essential. Without them, there will always be gaps in knowledge.

Especially in the biomedical field, collaboration is indispensable. You need to work with people from life sciences, biomedical research, and medicine. This explains why interdisciplinary work cannot exist without strong partnerships.

In biophotonics, for example, we not only need medical collaborators, but also data scientists, because we produce enormous amounts of complex data. These collaborations help us interpret and understand what we observe.

Modern interdisciplinary research simply cannot function in isolation. Collaboration is the key to progress.

Coming back to your question about the partnership between the Leibniz IPHT and the Institute of Physical Chemistry in Warsaw — the same principle applies. Both institutes have strong expertise in spectroscopy, imaging, and chemical sensing. This cooperation aims to bridge advanced photonic methods with molecular sciences, fostering cross-border innovation in optical health and environmental technologies.

Beyond research, such partnerships also strengthen European scientific integration. They enable the exchange of young talents, the establishment of long-term strategic cooperation in transnational photonics, and the creation of synergies.

To put it simply — collaboration allows us to achieve together what none of us could achieve alone. It is of utmost importance if we want to go beyond what can be done individually.

How important is it for scientists to draw inspiration from real societal problems? And how can that perspective shape not only what we study, but why we study it?

From my point of view, the most essential driving force in science is fundamental curiosity. We need to start from basic questions to generate new knowledge. However, I also care deeply about the societal impact of our research — what we can do with our findings to make a difference.

At IPHT we have the motto: "From ideas to instruments." It means that we begin with fundamental research, but we want to go further — to applications and, if necessary, even to developing instruments. In other words, we aim to cover the full chain: from fundamental science to application, and finally to translation into practice.

We have many examples where this has worked successfully — fundamental research that led to high-impact publications, and later to spin-off companies. Sometimes we start with what seems like a “crazy idea,” and it ends up as a commercial product.

Translation is part of our institute’s DNA. We have established structures that make it possible to turn scientific knowledge into real-world solutions. For example, we successfully applied for national funding from the German Federal Ministry of Research, Technology and Space to build an infrastructure that allows us to translate the latest photonic solutions for diagnostics and infection therapy much faster into products.

This new building will not only host advanced instrumentation but will also serve as a one-stop agency — a place where researchers or innovators can come with a proof of concept, and develop it into a medical product. We will also provide support for all regulatory aspects required to bring these products to the market.

In short, we aim to bridge the "valleys of death" between science and commercialization. This approach is part of the national roadmap for research infrastructures in Germany and has proven to be extremely effective in transforming scientific ideas into societal benefits.

What scientific directions or technological frontiers do you personally see as the most promising for shaping the next decade of photonics and its impact on human health?

I am deeply convinced that the convergence of artificial intelligence and photonics will define the future. This combination allows us to extract much more information from photonic data. If we can merge these data with other physical or physiological data — for example, from wearables — we can gain a much deeper understanding of human health.

Today, microelectronics mostly measures physical parameters such as oxygen levels, but not molecular information. Photonics, however, can provide molecular fingerprints. If we combine these two technologies, we move toward what I call the “optical-digital twin” of a person — a system that continuously monitors health status and detects early changes before symptoms become severe.

For example, we might use small, user-friendly devices that analyze a drop of blood from a finger prick to provide molecular information about immune cells or inflammation. This is not about fusing humans with machines — it’s about giving individuals simple tools to monitor their health and take preventive action.

White blood cells, for instance, hold a vast amount of information about our immune status and general health. If we can decode this information, we could gain unprecedented insight without the need for constant visits to a physician.

The first step, however, will be to create new tools for doctors — simple, “black box” instruments that provide immediate diagnostic information. We already have, for example, a Raman spectroscopy device based on fiber optics that physicians can operate themselves to determine whether tissue is healthy or diseased. The system is fully automated; no scientist is needed to run or interpret the data.

I also know that your Institute here in Warsaw, particularly the eye research centre ICTER, is doing excellent work in a similar direction — using optical technologies to study eye diseases. The eye, as we say, is the window to the brain, and this may even open new pathways to detect neurodegenerative diseases early.

There are many synergies between our institutes.

Citizen science has become an increasingly structured part of the research landscape in Germany and Europe, supported by organizations such as ECSA. How do you view its role in advanced research environments? Is citizen science practiced or encouraged at your institute?

Citizen science is more important today than ever before. It strengthens the connection between research and society.

Unfortunately, we have seen a certain erosion of public trust in science, especially during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Many people now believe less in scientific results. We need to rebuild that trust by showing, through direct engagement, how science benefits society.

At IPHT we work on many outreach activities to bridge this gap. One example is our comic character "Laser Girl." She helps explain what happens in the body when someone suffers from a severe infection such as sepsis, and how physicians and researchers can use photonic technologies to detect and treat it.

In the story, Laser Girl is miniaturized, travels through the body, and uses her laser to "fight" harmful bacteria. Of course, in reality, we don’t destroy bacteria with lasers — we use laser spectroscopy to identify bacterial species, understand the host response, and select the right antibiotic treatment.

The comic connects the fictional story with the real science behind it. It is freely available for download in the Apple Bookstore (currently in German; an English version is in preparation).

We plan to continue the series — for example, sending Laser Girl on an interplanetary mission to Mars or the Moon, where spectroscopy is also used in NASA missions such as SHERLOC, which employs Raman spectroscopy to search for traces of past life.

In addition, we engage citizens in other ways: through open days, the Long Night of Science in Jena, participation in the Highlights of Physics festival, lab tours, and partnerships with schools.

In our “Rent-a-Prof” initiative, teachers can invite our scientists to visit their classrooms and explain photonics or biomedical research in an accessible way. We are also planning studies involving healthy volunteers, who will contribute to data collection with wearables and blood samples, helping us explore new approaches to health monitoring.

All these activities aim to make science more open, participatory, and trusted by the public.

What would you tell young scientists entering today’s rapidly evolving scientific landscape? How can they remain bold and creative, yet grounded in purpose and integrity?

My first and most important advice: be curious. Be open to new things, and don’t be afraid of failure. Very often, ideas do not work immediately — that doesn’t mean they are wrong. You just need perseverance to refine your approach.

Second, work on something that truly excites you. Choose a field where you can imagine spending long hours without feeling burdened — because passion sustains creativity. If you love what you do, it will not feel like work.

I always tell my children — I have four — to do something they genuinely enjoy. When you love your work, you can spend hours immersed in it, and someone even pays you for doing what you love! That’s the best possible situation.

Finally, to be successful in science — or in any field — you must be bold, creative, and resilient. If you pursue your passion with persistence and integrity, success will follow naturally.

That’s a beautiful way to end this interview. Thank you very much, Professor Popp.

You are most welcome.

The interview was conducted by Dr. Anna Przybyło-Józefowicz.

Short professional profile of Prof. Jürgen Popp: Jürgen Popp studied chemistry at the Universities of Erlangen and Würzburg. After receiving his PhD in chemistry, he went to Yale University for postdoctoral work. He then returned to the University of Würzburg where he habilitated in 2002. Since 2002, he has held a chair in physical chemistry at the Friedrich Schiller University of Jena. Since 2006 he is also the scientific director of the Leibniz Institute of Photonic Technology, Jena. His research interests focus on biophotonics. Professor Popp has received numerous awards for his research, including the prestigious Pittsburgh Spectroscopy Award in 2016. In 2023, Jürgen Popp received an honorary doctorate from the University at Albany - State University of New York (USA) and the Charles Mann Award from the Federation of Analytical Chemistry and Spectroscopy Societies (FACSS).

- Author: Dr. Anna Przybyło-Józefowicz

- Date: 4.11.2025